THERE IS something like a Brothers Grimm fairy tale to the whole affair. The hope that many Americans harboured that criminal indictments against Donald Trump would break his near-decade-long stranglehold on the Republican Party has been dashed once, then twice—and now thrice.

In March, Mr Trump was indicted by New York prosecutors over alleged campaign-finance misconduct. Republicans shrugged; the former president enjoyed a surge in the polls. Then, in June, Mr Trump was indicted over the retention of highly classified intelligence at his Florida estate of Mar-a-Lago after he left the White House; after leaving the courthouse the former president stopped by a famous Cuban restaurant in Miami, as though it were an ordinary day on the campaign trail. On August 1st new charges were unveiled over the most serious of his alleged crimes: the attempt to overturn the legitimate election results in 2020 which inspired his supporters to invade the Capitol on January 6th 2021. Once again he basked in good feelings. “Thank you to everyone!!! I have never had so much support on anything before,” he wrote online. When it comes to members of his party, it is hard to dispute the claim.

Even his rivals for the presidential nomination are largely in lockstep. In a post on Twitter (now officially called “X”), Ron DeSantis, the Florida governor and his closest competitor, decried the “weaponisation of the federal government” and “the politicisation of the rule of law”. He admitted that he had not read the indictment, but argued that any trial conducted in Washington, DC, as the latest indictment would require, is a priori illegitimate because the jury would be constructed of those with “the swamp mentality”. Even in prior statements, Mr DeSantis has not seemed able to let go of the servility he displayed towards Mr Trump when his political career began its rapid ascent. He has previously pledged to sack Chris Wray, the director of the FBI, over his “weaponisation” of law enforcement—a thinly veiled reference to its investigation of Mr Trump.

The other candidates running against Mr Trump in the presidential race have put up similar defences. Tim Scott, a South Carolina senator, decried “two different tracks of justice”: “one for political opponents and another for the son of the current president”, a reference to Hunter Biden, who, for all his alleged crimes and vices, is a flimsy foil to Mr Trump. Nonetheless, the whataboutism is one that Republicans are obsessed with. The party’s congressional leaders—like the House speaker, Kevin McCarthy, and Elise Stefanik, the third-ranking House Republican—have even indulged in a bit of public conspiracy, explaining the latest indictment as an intentional distraction from new evidence they have uncovered in their investigation on the Biden family.

Vivek Ramaswamy, a wealthy entrepreneur and also a Republican presidential candidate, denounced the latest indictment as “un-American” and pledged to pardon Mr Trump if he were convicted. In a video statement, he blamed the events of January 6th not on Mr Trump but on pervasive censorship. “If you tell people they can’t speak, that’s when they scream. If you tell people they can’t scream, that’s when they tear things down.” It was a curious appropriation of leftish arguments: Republicans are not normally the people to agree with Martin Luther King Junior’s statement that “a riot is the language of the unheard”.

The few Republicans who break with this consensus seemingly command little public support for their position. Mike Pence, the former vice-president who defied his boss on January 6th but has often shied away from making too much of his stand, said that the “indictment serves as an important reminder: anyone who puts himself over the constitution should never be president of the United States”. Chris Christie, a former New Jersey governor, has appointed himself the chief antagonist to Mr Trump in the Republican primary. When commenting on the indictment over the mishandling of classified documents, he has cast the former president and his advisers as inept gangsters: “These guys were acting like the Corleones with no experience.” Neither man is scoring more than single digits in polls taken among future Republican primary voters.

Even the conservative institutions that have been less-than-fulsome supporters of Mr Trump have voiced scepticism over the indictment. The editorial board of the Wall Street Journal questioned the legal theory behind the charges, including relatively obscure crimes like “conspiracy to defraud the United States”, and argued that, however heinous his conduct on January 6th, the repudiation ought to be political rather than legal. The same is true of National Review, a conservative publication that has been expunged from many Republican circles for its criticism of Mr Trump, which argued that “it is not even clear that Smith [the prosecutor] has alleged anything that the law forbids.”

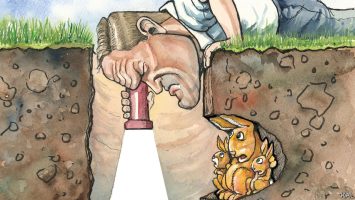

The prosecutions are about fundamental questions of the rule of law, but baser questions about politics are inevitable for a man seeking to reclaim the White House. Ask any Republican strategist what they think the impact of the indictments will be on the primary, and almost all say that it either does nothing to imperil Mr Trump, or simply grows his base of support. There is a hydra-like quality to Mr Trump’s appeal within his party: for every head that prosecutors attempt to decapitate, two more appear in its place. ■